About Turning Landscape

Turning Landscape became a Community Interest Comany in 2020 and is based at Ty Ebbw Fach in the former mining village of Six Bells, Blaenau Gwent, South Wales to develop ochre minerals - that form in coal mining landscapes as a result of the end of mining - to turn these into pigments for use as paint. In October 2022 Turning Landscape received Heritage Lottery Funding to suppor a programme of events, workshops, talks and demonstrations that bring together people with interest in the social, economic and environmental legacies of coal mining and extractive practices.

The research was developed by Onya McCausland and is now run as a collective community project CIC with Lucy Harding and Hywel Clatworthy as co-directors. We have a working agreement with the UK Coal Authority (a non-departmental government organisation) who provide us with access to their mine water treatment works, and use of the residue materials these produce.

Frances Mine Water Treatment Scheme, Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland 2014

This research programme has involved intensive engagement with places where mining and quarrying is still shaping the landscapes to observe and document evolving knowledge of particular sites, their geology, the mineralogical peculiarities and the effect mineral extraction has on the contemporary landscape. Each ochre forming in each landscape is geologically distinct and can be seen as an index of a place - formed from the specific environmental, ecologic, geographic idiosyncrasies of that place only.

Six Bells and Abertillery with the mine water treatment scheme just visible in the lower middle of the picture 2020.

Overlaying the material effects of landscape are the cultural complexities that are woven so deeply into each landscape structure that they become inseparable; the geological, the social; the ecological and the economic. The questions this work considers are can the complicated interdependencies between humans and geology be signified by a unique paint derived from waste minerals that form during the treatment of mine water? And can these colour materials that are unique to place be used, repurposed to restore pride and connection between community and landscape?

The coal mine ochre colours have a different genesis from traditional ochres as they are being generated through the treatment of polluting ground water in ex-coal mining regions across the UK. The unique geological setting of the individual landscapes has a particular and unique influence on the waste minerals forming there. The discovery of these qualities has happened through making artworks that follow five individual ochres from their geological landscape contexts through physical transition into usable pigments for paint. A process that simultaneously exposes layers of sociopolitical history, along with the contemporary cultural and economic connections to place.

Photograph of Tower open cast colliery 2015. Coal extraction at the Tower opencast

site came to an end in 2017 after changes in environmental regulations.

Photograph of Tower open cast colliery 2015. Coal extraction at the Tower opencast

site came to an end in 2017 after changes in environmental regulations.Ochre is the oldest of cultural materials with roots stretching back to the beginning of human history. The mine water ochres can be aligned with traditional historic ochre - a mineral that has been found sprinkled on cave floors, caked onto the buried bones of ancient humans;1 mixed with binder and turned into paint on cave walls, some 30,000 years ago and forming patterns on the built walls of early human settlements at Djade al- Mughara, Aleppo, Syria 11,000 years ago.2

Environmental impact

The mine water ochres forming in the vast subterrainian wastelands of the coal mines contain and carry the significance of a geological, ecological and social event in time that point towards the contemporary condition of past human and geological extractive practices occurring in a particular place in the world at a particular time in history. This work attempts to explore the complexity of these conditions - local and global, that are combined in a specific material. This research repositions each ochre colour as a culturally significant material as an acknowledgment of its real and symbolic significance in a long evolving human story. These ‘new’ mine water ochres are presented here as human colours with a very specific cultural story and value.

Six Bells and Abertillery showing underground mine workings overlaid with surface topography and infrastructure

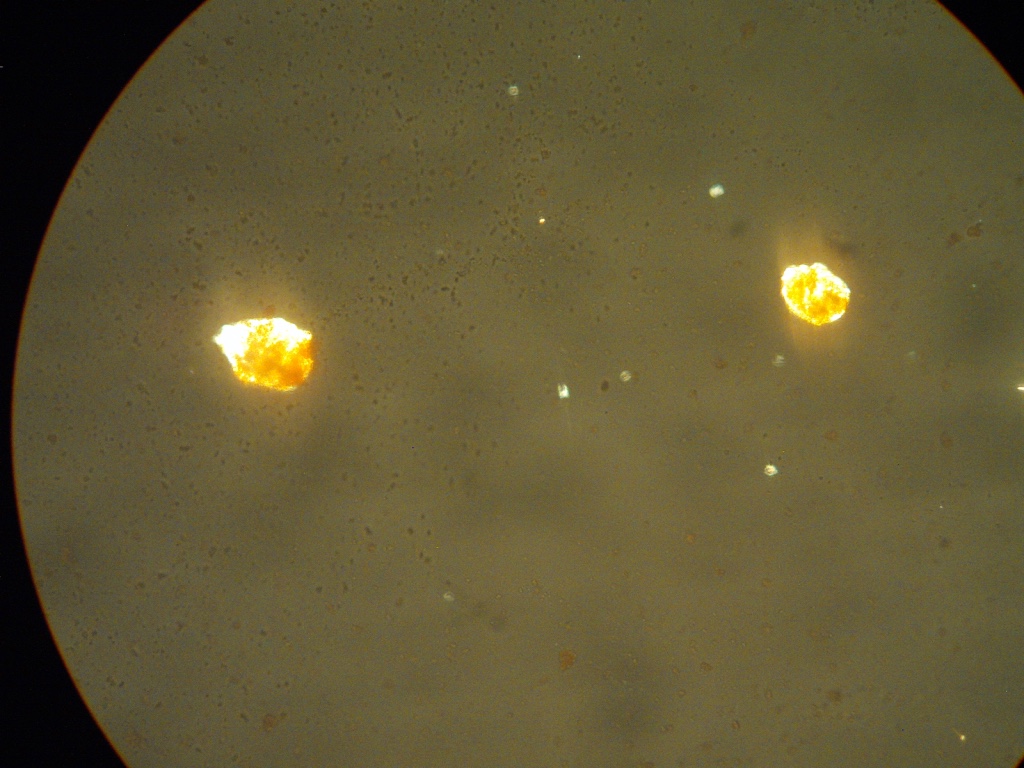

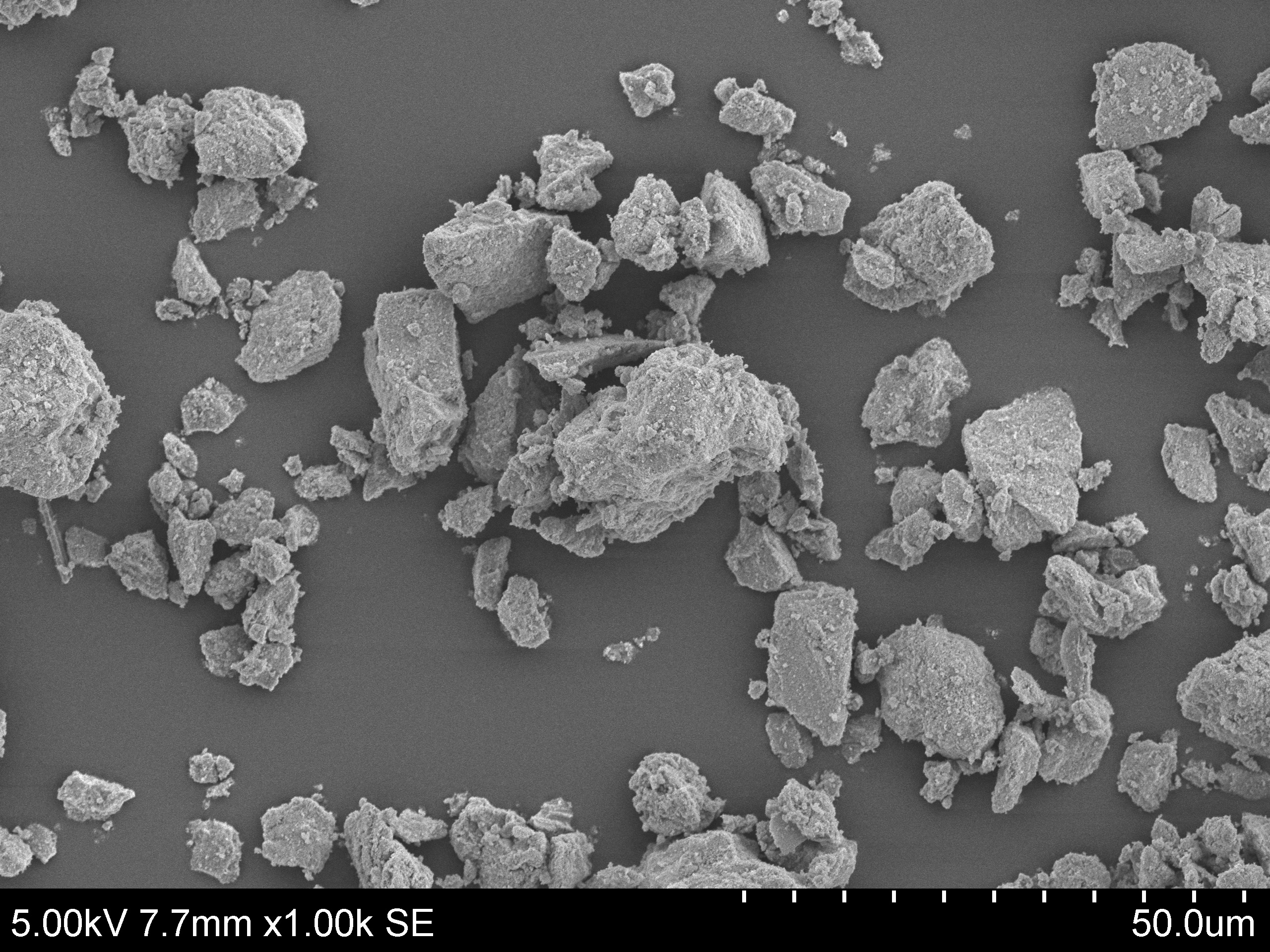

The research has developed and been informed through a focused practice of painting and its traditions, referring tothe earliest marks on cave walls, neolithic marks and the minimalist marks of the modernist / post modern traditions: Painting has been a line to follow and also to drift off from. Collaboration with chemists, earth scientists and paint manufacturers have helped to shape and understand the analytics of the material as pigment, from particle size, transparency and lightfastness, using x-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and cross polarised light microscopy, to drying, burning, grinding and sieving, scaling up, ratios of one medium to another to find a route to get a paint that carries the weight of the conditions of its formation, that can be applied to a wall.

Cuthill ferrihydrite digital photograph using cross-polarised Light (XPL) x1000, field of view 0.1 mm.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) Six Bells ochre

Coal Authority Video

In 2018 the Coal Authoity produced a short film oulining the processes involved in their mine remediation programme and ochre formation and how working with Onya McCausland brought new insight to the potential uses of mine water ochre for use in paint and how individual places produce different ochres colours. The film demostrtes the collaborative effort between Onya and the CA in working to change perception of the materials forming in the ex-mine sites.

Coming soon....

In the coming weeks we will be launching the very first sustainable exterior grade mineral based wall paints made from 100% coal mine ochres. And an amazing oil paint Six Bells burnt ochre made in collaboration with Michael Harding paints.

1 The Red Lady of Paviland: OUMNH Q.1. Visit to see the remains at Oxford Museum of Natural History 2016. One of the richest 1Palaeolithic sites in Europe is in South West Wales on the Gower Peninsula between Port Eynon and Rhossili. Sollas, W.J. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol.43 (Jul. - Dec., 1913)

2 National Geographic online: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2007/10/photogalleries/wip-week50/photo7.html, accessed: 217th December 2014. And: Caroline Cartwright (2008) The World’s Oldest Wall Painting In Syria?, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 140:1, 3-3, DOI: 10.1179/003103208x288645 http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/003103208x288645 Published online: 02 Dec 2013

Turning Landscape into Colour Abstract, link to PhD: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10039744/

Further info on individual artworks www.onyamccausland.com